What is Super-Resolution Microscopy? STED, SIM and STORM Explained

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Microscopes are valuable tools used in biological research. Traditionally scientists have used electron microscopes to clearly see subcellular structures or light microscopes to observe whole living cells.

The limitation with conventional light microscopes is resolution, which is defined as the smallest distance between two objects where they can be observed as separate objects. Because conventional light microscopes have poorer resolution than electron microscopes, scientists are unable to see subcellular or suborganelle details using these tools.

Thanks to advances in fluorescence microscopy, a type of light microscopy in which one wavelength of light is absorbed and another omitted, scientists can now use super-resolution microscopy to directly observe living subcellular structures and activities.

What is super-resolution microscopy?

Super-resolution microscopy (SRM) encompasses multiple techniques that achieve higher resolution than traditional light microscopy.

The resolution of conventional light microscopy is limited to around 200 nm due to the diffraction of light. As light passes through the surrounding medium in a light microscope, a single point of light (called a fluorophore) will appear blurry. The size of the blur is known as the point-spread function. When two structures are closer than the diffraction limit, they will appear as a single blur rather than two separate structures.

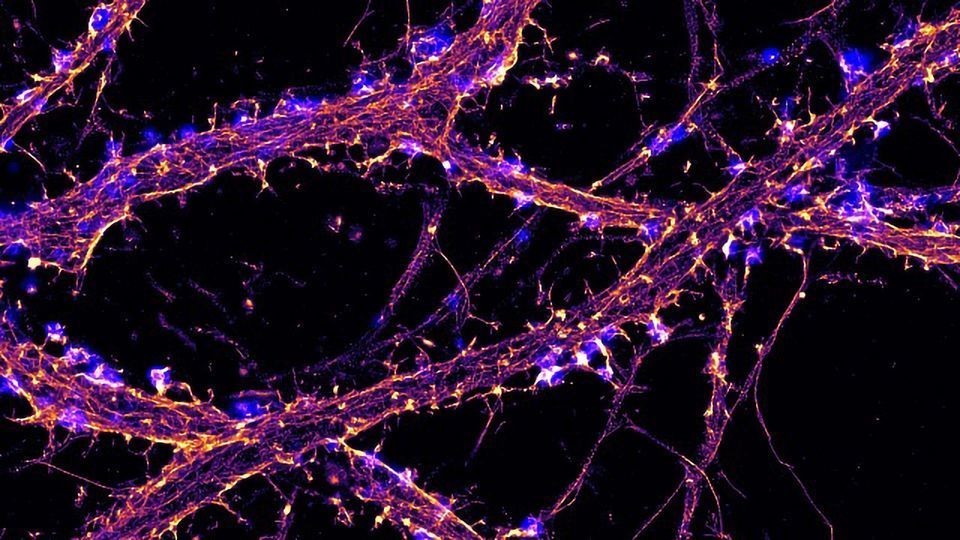

A STED (stimulated emission/depletion) micrograph image revealing actin (magenta) and microtubules (cyan) of a young dissociated hippocampal neuron. Image by K. Jansen and E. Katrukha, Kapitein Lab, Molecular and Cellular Biophysics, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

How does super-resolution microscopy work?

There are three main types of super-resolution microscopy, each one working via a different mechanism. These include stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, structured illumination microscopy (SIM), and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)/photoactivation localization microscopy (PALM).

What is stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy?

Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) Microscopy is a form of super-resolution microscopy that uses a technique called spatially patterned excitation. During STED microscopy, two lasers are used on the focal plane. When used together, the excitation laser and the STED laser reduce the effective point spread function (PSF). The lower the PSF, the higher the resolution.

The STED laser suppresses excited-state fluorophores located near the excitation focal point by a process called stimulated emission. A donut-shaped ring of fluorophores around the center of the image field is suppressed, whilst the center is not. The result is a PSF lower than the diffraction limit. Incredibly sensitive single-photon detectors then pick up the signal from the central fluorophores.

Saturated structured-illumination microscopy (SSIM) and reversible saturable optically linear fluorescence transitions (RESOLFTs) are other forms of super-resolution microscopy that use patterned excitation to enhance resolution.

What is structured illumination microscopy (SIM)?

Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) is used to increase the spatial resolution of light microscopy. A fluorescent sample is excited multiple times using striped illumination patterns. Each time the orientation and position of the stripes are changed.

These images are analyzed using computer software that looks at Moiré patterns. The stripes fired at the sample interact with high frequency light produced from the sample. This interaction produces a third pattern that can be more easily analyzed. Using multiple images, further detail is obtained, and an image is reconstructed with around twice the resolution as traditional light microscopy.

The benefits of SIM include:

- Live cell imaging

- 3D imaging

- Thick section imaging

What is stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)?

STORM, part of a family of single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) techniques, activate or excite only a small percentage of fluorophores at one time, reducing spatial overlap and allowing images with as little as 5 nm resolution.

STORM combines photoswitchable dyes and a lower power activation laser, blinking or switching from dark or off states to emission or on states. By imaging the photoswitchable fluorophores over time, it is possible to identify the precise location of these molecules. First unveiled in 2006, STORM is one of the newer forms of super-resolution imaging.

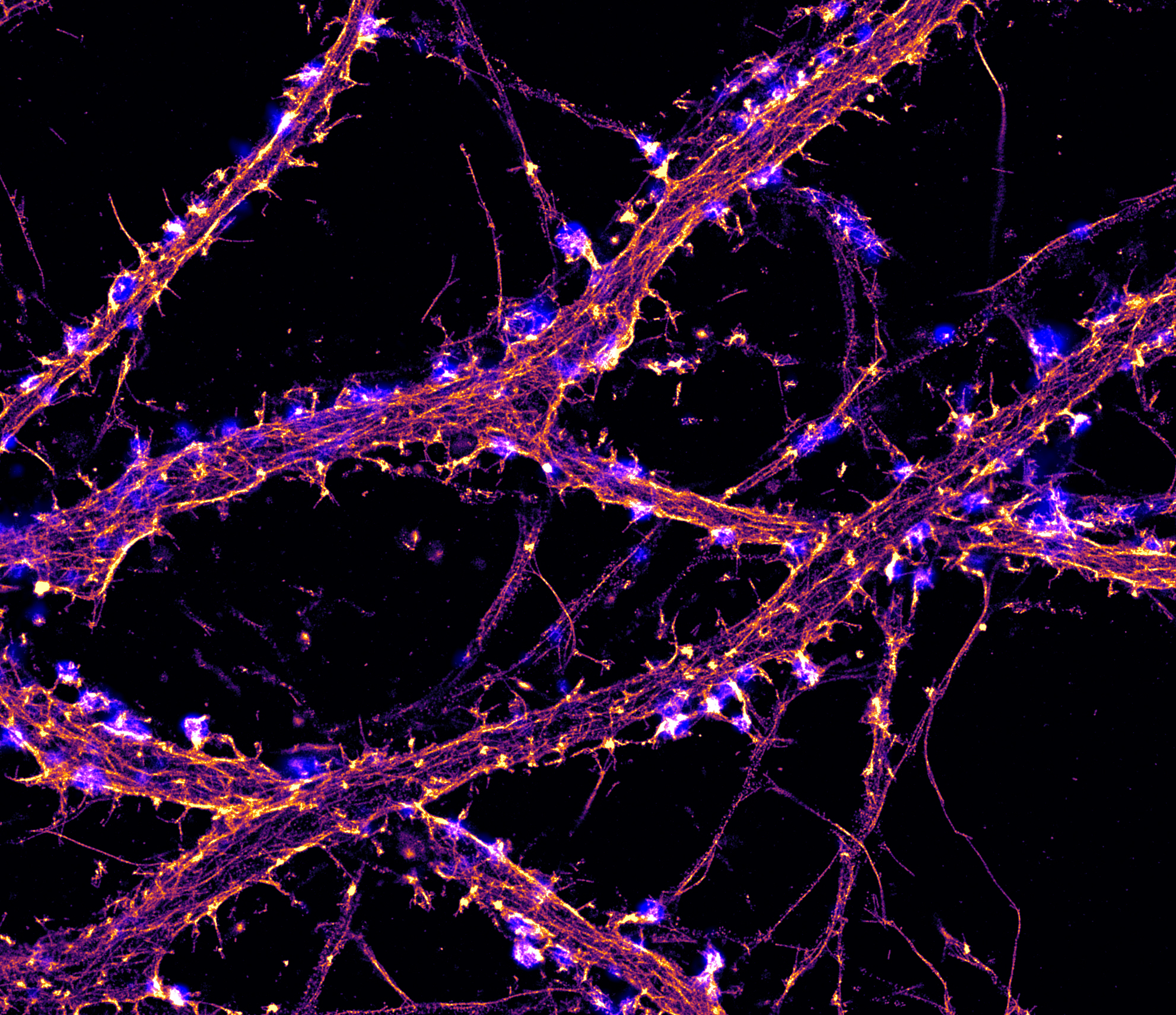

Hippocampal neuron labeled for actin (orange) imaged by STORM and synapsin (blue) imaged by TIRF. Credit: Christophe Leterrier, NeuroCyto Lab, INP CNRS-Aix Marseille University, Marseille, France.

What is dSTORM microscopy?

There are two types of STORM. The first type of STORM uses an activator dye and a reporter dye. The activator dye switches fluorophores on, and the reporter dye results in a signal. The second type of STORM, direct STORM (dSTORM), does not require an activator dye. During dSTORM, commonly used fluorophores can be combined with specialized buffers and lasers to induce photoswitching.

What is two-photon excitation (TPE)?

TPE is an optical process that uses multiphoton absorption to image live samples, resulting in less phototoxicity than conventional confocal microscopy. Two-photon microscopes use infrared excitation light to penetrate further into tissues and with minimal scatter compared to exciting at longer wavelengths. For each excitation of the fluorophore, two photons of infrared light are absorbed, and excitation is limited to a tiny focus volume, so there is less contribution from out-of-focus fluorescence.